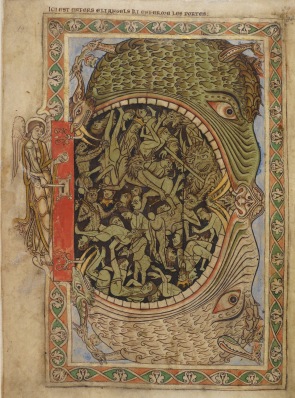

Images above: the Winchester Psalter, British Library Cotton MS Nero C IV – Herrad of Landsberg, Hortus deliciarum – The Tree of Life, Gua Tewet, Borneo

“Radical professionalism” goes beyond “professionalism” and returns the latter to its deep true conservative sense. This is the longest in a series of posts. The project started with thinking about con– and pro– words in spring 2016, in relation to local (university) current events. The first “deliverables” were some images at the end of a self-flagellating work in progress post in July and a preamble in mid-August. Then followed two posts looking at what professionalism is not, on false values that will be very familiar to readers of Medieval allegory and satire: a first post on neutrality (false balance) and a second post about appearances (seeming, or: false being and false value(s)) and their connection to appropriateness, propriety, and property. There were two other entremets posts (here and here). This present post looks at what professionalism is; and what, in the shape of a radical professionalism as modelled by radical academic professionals, it could be. [UPDATED AFTER POSTING TO ADD] In a fourth post, we’ll see how radical professionalism actually exists, in the world of Medieval Studies.

In the time that has passed since I started drafting this post, several things have happened. The new academic year meant that other reading and writing took a back seat to primary professional work: that is, in the main current sense of the term, that work for which I am paid. The first week of term meant working around twice the number of hours that count as “full time” in other professions; including extra work to replace another instructor; at the end of which, I simply did not have the energy to do any substantial thinking about anything else. I did make a note of the approximate time at which I had worked 37 hours, then 40 hours, then 48 hours: the former being international conventional limits to the working week, the latter being one of the maxima for medical professionals’ work. I considered the curious fact that I did not, after those times had passed, then stop work and stop thinking about work. In other professions, I would have done. Academia is different. Last week, the second week of term, settled down progressively, but included some thinking about “professionalism” in relation to some current events. And now, today, to these events we should add the feast of Hildegard of Bingen.

Some warnings would be in order at this stage in an introduction.

Image above: The New Yorker, 16 August 2016.

I am by birth and upbringing a European, by which I don’t mean the newfangled colonialist Americanism but actually European: a mongrel multilingual multicultural migrant, of and growing up in Europe, raised as an experimental anti-nationalist internationalist cosmopolitan européenne sans frontières.

I am, amongst other things, a medievalist. My doctoral work was in medieval French and Occitan literature. My basic training was old-fashioned: my first superviser was the late Karl D. Uitti; after his death Sarah Kay supervised me, and the other readers with whom I worked on my committee were John V. Fleming and François Rigolot. This post contains conservative (in the “conservationist” sense) philology and refers to that part of Medieval Studies that is about western European literature and religion. (There are many other parts of Medieval Studies and many ways of being a Medievalist.) I am fortunate not to be working on the “hottest” areas of medievalism, England and North-West Europe; though my own area has been hijacked by nationalist extremists, white supremacists, and haters of religions not their own: see for example the use, misuse, and abuse of Joan of Arc by Vichy and FN propaganda. We’ve witnessed an increasing politicisation and polarisation in perception—especially over the last year and in the last few days—of western European history, culture, and values.

That should not be a reason for side-stepping The Issues, “being properly scholarly,” putting one’s head down and passively or actively attempting to purify the field of politics. To do so would be a pampered abuse of priviledge and power, second-rate unimaginative thinking associated with second-rate unintelligent scholarship, through a dispassion that is the opposite of compassion. The opposite of Dante’s donne ch’avete intelletto d’amore.

There is no excuse for reducing The Issues to a false binary—and the confusion of equality with equity—in which equal weight, space, and time is accorded to two sides; an artificial pseudo-reasonable nice clean simplified dialectic does not truth, virtue, or justice make; and no, that is not “how to be professional.” We have already discussed the errors of “both sides,” false balance, and misplaced “neutrality” in part (1) of this series.

And no, the presence of Issues is also not a reason to avoid or abandon the field, or to abandon it to a group that one deems extremist or destructive; nor to stop thinking and talking about those very areas that have become most contentious.

Au contraire: now is the time to work most seriously and intensely on those very “Values of Western Civilization” while they are in mortal peril of corruption. That is the term that feels most apt, my mongrel upbringing having included liberal-to-left-wing social-justice Catholicism. Direr still: those values risk annihilation. Throwing the baby out with the bath-water would be a disgraceful disservice to scholarship and knowledge—the height of academic unprofessionalism—and the more tragic for wasting that marvellous infant’s potential to bring redemption.

I will not be claiming that this mythical creature that I first met in the USA, “Western Civilization,” is a pure untainted glorious summum bonum. That would be an ignorant, deluded, and/or foolish claim. Part of our creature’s marvellousness is its messy complication, including the human and monstrous and flawed and evil. It would be an insult, injury, and injustice as much as an untruth to claim otherwise. It is paradoxically the most fervent advocates of Western Values who pose the greatest threat to that which they claim to defend: wolves in sheep’s clothing, la robe ne fait pas le moine. Turning a lively intelligent force into a cardboard cut-out caricature, a pawn in a game, an innocent sacrificial lamb? Twisting it to be used against its nature and for an alien higher (i.e.: lower) end? Using it for hate, harm, and hurt? Grotesque, selfish, hubristic, and a gross abuse. Breaking the commandments (especially the new one); failing to perform the works of mercy; embracing greed, envy, wrath, sloth, and pride. And therefore, if you believe in such things (or their translations): imperilling the sinner’s immortal soul.

This post has as premises:

(1) that words have meaning, a meaning which includes their entire past history

(2) that knowing more about a word and using it caringly and carefully is important—as a mark of respect for the word and for meaning itself—and can also contribute to understanding; we have seen the dangers of doing otherwise here.

The short version of this post: the main claim is that (western European, Catholic) medieval monasticism offers some valuable insights into “professionalism” through breathing new life into the ideas of vocation, swearing, oaths, promises, and words having meaning and weight especially when used by expert word-professionals. Be that with or without religious faith. I am not going to talk about my own religious faith, nor even about whether or not I have any at all: that is no-one else’s business, and if we can thank the Protestant Reformation and the Enlightenment and French Revolution for one thing, it is for freedom of private individual conscience. Today may be one of the few occasions on which I will ever praise Modernity.

And now for the long version, which will be accompanied by the music of Hildegard of Bingen. This post is long. Singing may help.

STEP ONE: PUT THE “PRO” BACK IN PROFESSIONALISM

The pro– prefix to “professionalism” is an essential integral inalienable part of its meaning. “For.” This pro is what creates association: togetherness, relationship, socially bound to one another and into a whole. It means being part of a community, doing things for it, standing with and standing up for colleagues (connecting pro and cum), and doing so in communion. Pro is for all one’s fellows, of all sorts and ranks—from lowest to highest, newcomer to retiree, novice to pope, occasional part-timer to intensive narrowly-focussed obsessive, powerful and powerless, in richness and poorness, in sickness and in health, in equity and diversity—united in fellowship. Radical professionalism is brotherhood, sisterhood, making and maintaining kith and kin. It may also be radical in a secondary sense, of being fundamentally anarchist.

STEP TWO: MAKE PROFESSIONALISM PROFESSIONAL AGAIN

It would already be a good start to return “professional” to its earlier meaning, in relation to skilled trades.

Craftsmen’s guilds; artists and artisans; the old trades and professions; more recent additions to the list of occupations requiring training, experience, and knowledge: the two required qualities for being a professional are expertise and adhesion to a code of conduct. The foundation for professional membership is a promise, made by solemn sacred oath, to uphold that code, on the basis of which one can offer one’s word of honour to those with whom one interacts in one’s capacity as a member of that profession to conduct oneself honourably. See also: chivalric codes, oaths of fealty, diplomatic treaties, and any formal agreements.

Membership of that profession is a public guarantee of acceptance and active enactment of its code. One is trustworthy, in activities to do with that profession. One’s word is one’s bond. This does not, of course, mean that one is or should or could be held to be equally trustworthy, responsible, or accountable in all things in the same way: just in that professional part of one’s life.

Image above: The New Yorker, 27 December 2016

One’s professional word is a deeply serious matter. It requires intelligent thought, questioning, understanding, and full free informed consent. I’ve met this in non-academic capacities when joining the Booksellers Association (UK), and becoming a Member of the Chartered Institute of Linguists. We are not talking about the “professional ethics” that reduces ethics to box-ticking, training-exercise-completing, certification-achieving, project-managing compliance culture. Simplification, simplistic flow-charts and action plans, steps to follow to ensure that you have Done The Right Thing in the right approved way, to ensure standardised procedure. A mechanical process that involves no questioning, thought, reflection, consideration, responsibility, and judgement. The current perverted sense of “professionalism” should be avoided as it is a mechanical, dehumanising, anti-ethical, unquestioning error. It should be embarrassing that the Laws of Robotics (Asimov, Dilov, Kesarovski, Ashrafian, Harrison, Sottilaro) set a higher ethical standard:

STEP THREE: PUT PROFESSING BACK IN PROFESSIONALISM

Here is an formal profession that I made when I was eighteen:

1. A person shall be deemed to be matriculated from the beginning of the term in which a completed Matriculation Registration Form and satisfactory evidence of his or her qualification to matriculate are received by the Registrary.

2. Every candidate for matriculation shall subscribe to the following declaration by signing the Matriculation Registration Form:

‘I promise to observe the Statutes and Ordinances of the University as far as they concern me, and to pay due respect and obedience to the Chancellor and other officers of the University.’

(I wrote in a large book; there is also now an online version.)

There were of course plenty of other rules, and College rules, and most of them seemed to be eminently sensible. (Being a geeky child and as I was doing my Part I in Law, I did actually read the rules.)

Rules governing any group of individuals who change their habits and come to live together in close quarters are for the most part flat-footedly practical common sense. It is here that we see the goods of “professionalism”; even those behind the problematic recent notion of “seeming professional.” Being clean, not smelling or looking or sounding offensive: for the comfort of others around you and to prevent the spread of disease. This is basic: a minimal standard of behaviour for a social animal, let alone a domesticated one in human civil society. Recognising that you are living in society, and showing consideration to others around you. Behaving in a way that doesn’t harm others. Thinking before you act. Acting responsibly. Basic stuff, but difficult nonetheless: it is much easier to try to do good than it is to try to avoid doing harm. I’ve done this. I’ve got it wrong. I’m sure that is true of everyone I know.

For another example, see the UBC Respectful Environment statement and Academic Freedom policy. Here’s an excerpt from another behavioural rule:

Colleagues working in other periods and cultures will find that many other examples of this basic human phenomenon come to mind, supplemented by their own personal past histories. Here is the OED entry for “profession”:

And Canon Law on vows and oaths:

“Profession”—pro + fess ; profiteor, profiteri, professus sum—is rooted in Benedictine monasticism. Like con-fession, pro-fession is a public speech-act with and before others; a declaration of faith, a solemn binding promise, by which one becomes a member of that collectivity; and through which community and collegiality are created and common shared values maintained, with the participation and witnessing (and communion) of all. Here is a nice multilingual example from Syon Abbey via the University of Exeter Syon at 600 project:

And a translation of the Benedictine rule, ch. 58, “On the Manner of Receiving Brethren”:

(For medieval Latin examples, see British Library Arundel MS 155 and Harley MS 5431.)

The exact wording of the vows may need some translation (in the strict and broad senses), but in all the cases above we are looking at variations on the evangelical counsels of chastity, poverty, and obedience (or stability, conversion of manners, and obedience)—restraint and renunciation, in short—as supererogation beyond the expected ethical minimum of the Ten Commandments; and a public declaration by which one joins the con-secrated life.

These different standards distinguish this root form, the radical idea, of professionalism. The old professions—medicine, the law, theology—served and serve a higher end (saving health and bodies, saving souls, justice), at the service of others, and as vocations (like “profession,” that word has a public spoken promise at its root); and with dedication, devotion, and care.

“Professions” put vocation first. “Trades” put profits first. Both may well involve both vocation and profit, in various kinds of balance. Unselfishness and self-abnegation, while rare, are not necessarily incompatible with commerce. The world would surely be improved were professions and professionalism to be more professional. Learning more about themselves by learning about their own history would be a good start, like any self-examination that precedes an examination of conscience and all that follows on the path to self-knowledge and true self-improvement.

The idea of “being a profession” includes other kinds of work besides the aforementioned three—such as university or other teaching, via the fourth western European medieval university faculty, Arts (vocation: save knowledge)—but the idea of “vocational” is losing its sense of service and higher standards, just as “professional” is. We’ve seen the same profession/professionalism issues with noble/noble-seeming and “aristocracy” changing in meaning from “rule by the best” to “rule by those born to it,” with a need for new terms like “meritocracy”.

Meanwhile the noblest of pursuits, “otium,” becomes an immoral vicious idleness, laziness, counter-productivity, and destructiveness; as opposed to a “negotium” (and “officium”) that changed from being what one does to support oneself and to give one the time and energy for “otium.” It is “negotium” that is now perceived as moral, virtuous, productive, and by definition constructive. Not because it actually creates; but because it leads to profit.

A return to the roots of what it means to be a professional—embracing radical professionalism—could help us to break those chains of profit and interest, bring us back to our vocations, and free us and our beautiful minds for higher purposes.

Three moments in the history of western European religious orders:

(1) 5th c. CE: Benedict of Nursia

(2) 13th c.: Jean de Meun, Le Roman de la Rose

Je ne l’oi pas plus tost passee

Qu’Amors trouvai dedanz la porte,

et son ost qui confort m’aporte.

Dex ! quel avantaige me firent

li vassal qui la desconfirent !

De Dieu et de saint Benoait

puissent il estre benoait !

Ce fu Faus Samblant, li traïstres,

le filz Barat, li faus ministres

de Ypocrisie sa mere,

qui tant est au vertuz amere,

et dame Attenance Contrainte,

qui de Faus Samblant est enceinte,

preste d’anfanter Antecrit,

si con je truis an livre ecrit.

Ne sunt religieus ne monde ;

il font un argument au monde

ou conclusion a honteuse :

cist a robe religieuse,

donques est il religieus.

Cist argumenz est touz fïeus,

il ne vaut pas un coustel troine :

la robe ne fet pas le moine.

Guillaume de Lorris & Jean de Meun, Le Roman de la Rose, ed. Félix Lecoy (Paris: Champion, CFMA: 1965-1970): t. 2, v. 11021-11028.

This romance also has brilliant passages about freedom of expression, which are worth reading in their own right and in their 15th-c. reading and debate, the Querelle de la Rose started up by Christine de Pizan. The debate’s arguments may look familiar to anyone who deals with freedom of speech, misogyny, satire, social justice, and artistic licence; my own position is complicated and changes on every rereading and with everything that students bring to them every time I teach these texts.

(3) 17th c.: Molière, Le Tartuffe.

This was the last set text in a course I was teaching in July-August, while first thinking about this post.

Hypocrisy, lies, and deceit are nothing new in 2017; nor can they be blamed on an increasing secularisation of modernity and post-modernity (or whatever it is that we’re supposed to be in now, other than “hopefully still in the middle and not in end times”). Questioning appearances and distrusting someone’s word are not new. If anything, our 13th-century example shows a more sceptical, free-thinking, and intelligent approach than many we’ve met the last couple of years. Nor is it new to value trueness and watch out for it: that central part of the Roman de la Rose is also worth reading for the Faus Samblant (“false seeming”) incarnation of the liar paradox, harrowing moments of sincerity that are disbelieved and mocked, and revelations of truth.

STEP FOUR: PROFESS

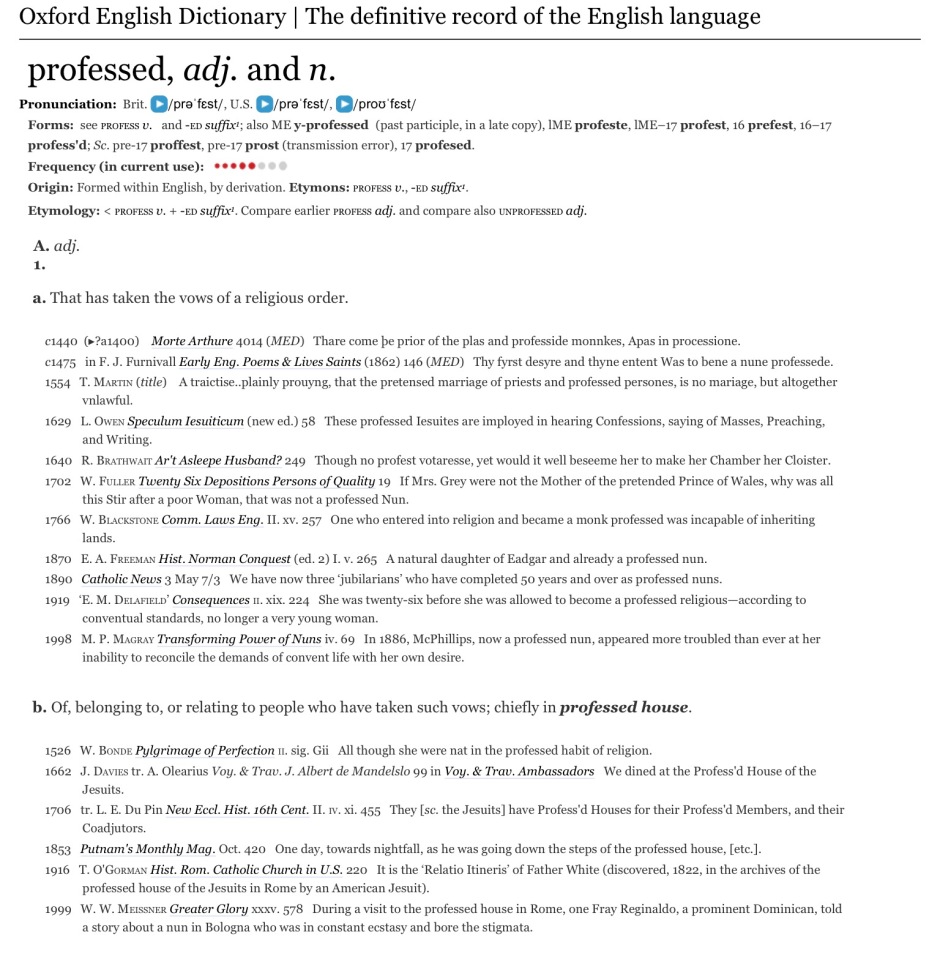

Here is the OED again, to show how “professing” works. There are some wonderful obsolescences that, just as “dead” languages are really “sleeping,” could be reawakened:

In the first post in this series, we looked at the relationship between “professionalism” and “profession” as being akin to that between “Marxism” and “Marx.” Another analogy would be the relationships of Evangelists, evangelism, evangelicals, and evangelicalism. We see a first “~ism” with 16th-c. humanist scholars, reformers but not necessarily Reformation; and then later developments of that lexical grouping, to include fundamentalists who are quite the opposite: against scholarship, sceptical questioning, free thinking criticism, humanism; and yet (thinking of Anabaptist and dissenting movements and their descendants), let us not forget their fundamentally humanist questioning of infant baptism, with entry into a religious faith being instead by choice, by an adult capable of making such decisions.

I’d wondered if there might be a term that would work better than “professionalism”; “professionalicalism” perhaps? “Professism”? Or should we reappropriate and queer “professionalism,” fight back and rage against the dying of the light?

Like fundamentalist evangelicalism, radical professionalism is a reaction to threat, a worry about loss, and a fear of total destruction. Substituting values for value, professionalism has sold its birthright for a mess of pottage. It is empty. Worse: bereft of the ability to have meaning, to be meaningful, and to make meaning, it cannot fill that void. “Professionalism” has lost both the letter and the spirit of the word. It has lost its sense, lost its way, lost itself.

Words and meaning matter.

The threats to “professing” from “professionalising” and its false seeming are not new. Over to the OED again:

Professing. Making public declarations. Choice. Consent. Conscientiousness. Speaking out publicly.

We should swear more, and do so deliberately.

I don’t (just) mean that as a Scottish-Northern Irish-Irish person whose background cultures (ex. Glasgow) include oathy sweariness. Professionalism includes swearing less; ideally, not at all. Radical professionalism would include swearing more, making vows more often, being more outspoken, and meaning it; in public situations when speaking and acting as a member of a profession.

We should resist empty language, neutered unbeautiful apoetic speech, and corrupted “professional-sounding” NewSpeak creep.

We should use words and mean them. Weigh words and make them weighty. Scholars deal in words—particularly but not exclusively those of us in the liberal arts and humanities—and, as that is one of our areas of professional expertise, what we say matters. Our words already carry more weight.

Scholars of all ranks already have that power and potential for influence. We should already be using our word-power in the service of knowledge. Why not also use it for good, in the service of others less powerful and priviledged in eloquence and in the ability to speak out or to speak at all?

Perhaps we can help to raise standards in public discourse of all kinds. Whether applying the term “professor” broadly for all professed academic faculty, or in the strict sense of tenured research faculty, or the strictest sense of holders of professorial chairs: radical academic professionals should be more professorial, in keeping with the full sense of “professor” and its emphasis on meaningful public speech:

Being radical professionals will sometimes mean declaring and emphasizing, in public speech, that we’re not speaking as scholars or academics: we are of course still human beings like any others, and that includes having several metaphorical hats in our wardrobes, some of which are worn separately and some together. An academic is also a private person with a private life. And an academic is also a consumer, dog-walker, volunteer, taxpayer, bus passenger, patient, voter, parent, member of neighbourhood association, sportsperson, passer-by in the street, activist, recluse, local in the pub; a citizen.

If academia is related to monastic orders, this can be in extension of the ideas and ways of being in the world that are at the heart of orders like the Franciscans, Béguines, and Jesuits; living with and in the world, even if that means living a more complicated life.

Just as there is a plurality and diversity of religious vocations, there are also many ways of being a radically professional academic. Academics, like any other citizens in a free country, can decide how they wish to live their lives, and how far they wish their professional lives to involve those other spheres that are public and private life. To continue the religious analogy, our scholarly vocation can also change through life. It can mean: moving up in the order (department heads and deans) or from a regular order to a secular career (management and administration, who occupy the place of the priesthood and episcopate in this analogy); or leaving the world, to live apart from it in more rigorous closed forms of coenobitic monasticism or in eremitic ascetic solitude.

Radical professionalism is diverse.

STEP FIVE: FROM PROFIT TO PROPHECY

Academic radical professionalism ought to be free of worldly interest, of power and profit; devoted to greater, longer-term goods.

Returning to Faux Semblant in the Roman de la Rose:

l’ort hypocrite au queur porri,

qui traït mainte region

par habit de religion

v. 10442-10444.

Je suis des vallez Antecrit,

des larrons don il est escrit

qu’il ont habit de saintée

et vivent en tel faintée.

Dehors semblons aigneaus pitables,

dedanz somes lous ravisables.

Ibid., v. 11683-11688.

Qui de la toison dam Belin

au leu de mantel sebelin

sire Isengrin affubleroit,

li lous, qui mouton sembleroit,

por qu’o les berbiz demorast,

cuidiez vos qu’il nes devorast ?

Ibid., v. 11093‑11098.

Lupus greca dirivatione in linguam nostram transfertur. Lupos enim dicunt illi licos, licos autem grece, a morsibus apellantur, quod rabie rapacitatis, queque invenerint trucidant.

The Aberdeen Bestiary, Aberdeen University Library, MS 24, f° 16v°

For further rapacious wolves, see for example Jonathan Morton, “Des loups en peau humaine : Faux Semblant et les appétits animaux dans Le Roman de la rose de Jean de Meun,” Questes : Revue pluridisciplinaire d’études médiévales 25 (2013): 99-119. https://questes.revues.org/107. And Kathleen Davis, Karl Steel, etc.

Radical professionalism could go beyond regular (that is to say: secular) professionalism in restoring trust, confidence, harmonious workplace relations, and a work/life balance; contributing, in capitalist / neoliberal terms, to greater efficiency and productivity through a low-cost investment in wellbeing. In environmentalist terms, radical professionalism encourages sustainable long-term forward-thinking stability in a richly biodiverse ecosystem. In university and political terms, radical professionalism is a creative, constructive, critical way to resist invasion and colonisation by external corporate values, their unconsenting imposition of government and administration by an upper echelon of non-academic professionalised leadership, and their rapacious commodification of the university for profit.

We could instead return academia to being a collective thinking body formed of its faculty and students (and emeriti and alumni), in conjunction with support staff colleagues, as a harmonious shared workplace in which we work in mutual respect. That happy ideal could and should, as in many an example of a well-functioning abbey, include our administration: and everyone else from abbess or abbot to a passing visitor given hospitality for a night or a stranger given an hour’s rest in a garden.

In remembrance of Eric Vatikiotis-Bateson: “work should be fun.”

It’s a radical idea. It’s also another expression of those ideas of radical professional vocation. It does not mean that one works all the time, or for free, or that because one enjoys it one shouldn’t be paid for it because fun is its own reward, or that work and fun are entirely separate things and the reason that work is paid is in recompense for taking you away from your fun; volition, volunteering, and voluntary should not be associated with that false freedom of “for no money” and especially not when that translates to a further sense of “free” that is “for the profit of someone else who has not worked.”

Work is work. I say that as someone whose first full-time work, as a bookseller, was a very low-paid job but one of the most rewarding I’ve had, and with the greatest benefits. And I say that as someone who thinks about work off and on a lot, and about things associated with work, and who reads more or less constantly when possible. Add all my reading and thinking time, and cogs turning in the background, and work expands to fill every waking hour of every day. This is a peculiarity of scholarly life; it’s difficult to manage, and there are many ways to do so. In my own case, there’s the added complication that pretty much anything I read will have some connection with something to do with work: with teaching and learning about languages, literature, culture, the medieval and medievalism, speculative fiction, the imagination. Everything I read, and many random things I bump into, and potentially anything I see. As my mother puts it, I can’t switch off. It may be some sort of spin-off from childhood hyperlexia. I’m used to it; I also remember a feeling of luminous joy, when talking about this phenomenon with my first PhD supervisor, at being reassured that actually this was OK and indeed an asset. It’s a manageable condition.

I can sort of switch off. I can and do also drift: at Mass when a child, walking in woods and gardens, listening to music, on beaches with waves rolling in and stones to consider. Birds at the feeder on our balcony, squirrels and crows in rubbish-bins, and the inhabitants of tidal rock pools are an intermediate category of activity as they rapidly turn into stories; blame Calvino.

A vocation need not mean burnout; it can be a balance of public and private, of work and prayer and rest, with flow and intersections between them. Pax, ora, et labora.

We could do worse than to model academic community on Benedictines, such as Hildegard’s abbey of Bingen. It’s easier to see the privacy and appreciate the freedom of hermits and anchorites. Religious living in community have time for privacy too—solitary silence, contemplation, meditation, prayer, communion with the divine—outwith participation in their community and the control of institutional authorities, their order, or forces of the outside world. Of course, this all changes if and when you tell others and write things down: sometimes visions will stay within a community, sometimes they will be spread outside it, but usually (and ideally) with the consent of the visionary. Thus, while some are martyred, others are tolerated and protected, or change their community, or their order, or found a new one; sometimes this will have negative consequences for a community (ex. Béguines). Monastic and nuntastic communities ebb and flow. They are living dynamic ecosystems. They aim for harmonious sustainable continuity, coexisting with an outside world around them, or interacting with it, but either way as low-impact islands of calm in balance with their larger environment.

STEP SIX: RADICAL ACADEMIC PROFESSIONALISM

Let us go further back, to end this very long and serious piece with some puns. Here, from the Anglo-Norman Dictionary, are “professer, prophiter, propheter” and associates:

Let us profess, then.

Let us move from professionalizing to professizing.

If the idea of “professing” can changed to be conflated with “profitting,” there is no reason that “professing” cannot be returned to its original root core true self, rescued from the corruption of capitalism … and remedied with the addition of “prophesying.” For that is the mysterious magical extra thing that academic, scholarly, thinking, intellectual workers do. We do creative and critical work, we imagine, we innovate, we make the SF of speculative fabulation, we think ahead and outside and beyond. Thinking again of Eric’s memorial on Saturday: we shouldn’t just think outside the box. We shouldn’t be looking around to check if there are boxes. We shouldn’t be seeing boxes there at all. There is no box. And, like the child in Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Emperor’s New Clothes,” we should say so.

Let’s not “act professionally.” Let’s BE professionals: radical professionals; and let’s be prophets against profit and for values in ours, the most radical profession.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

The Aberdeen Bestiary. Aberdeen University Library MS 24.

Benedict of Nursia. Regula S.P.N. Benedicti via The Latin Library; Leonard J. Doyle English translation as St Benedict’s Rule for Monasteries via Project Gutenberg.

— in British Library Arundel MS 155 and Harley MS 5431.

Codex Iuris Canonici. Latin text via the Vatican; English translation as Code of Canon Law, via IntraText and the Vatican.

Guillaume de Lorris & Jean de Meun. Le Roman de la Rose, ed. Félix Lecoy (Paris: Champion coll. “Classiques Français du Moyen Âge,” 1965-1970).

— online, along with over 130 of the manuscripts, at the Roman de la Rose Digital Library.

Molière. Le Tartuffe. Text online at toutmoliere.net; the 1669 edition (amongst others) is online at BNF Gallica.

Morton, Jonathan. “Des loups en peau humaine : Faux Semblant et les appétits animaux dans Le Roman de la rosede Jean de Meun.” Questes: Revue pluridisciplinaire d’études médiévales 25 (2013): 99-119. https://questes.revues.org/107.

The Oxford English Dictionary..

Statutes and Ordinances of the University of Cambridge.

UBC Respectful Environment Statement.

Credit for images and commentary thereon via #medievaltwitter (other than my own):

@alexewan

@BLMedieval

@cmcurran21

@emilie_nadal

@melibeus1

@ParvaVox

@PiersatPenn

@SariRautiainen

@UoEHeritageColl