In the literary / literate humanities, even if we’re not in times of crisis, we—faculty, students, the impersonal cultural entities that are academic programmes, faculties, universities, and societies—sometimes like to think about literature in a curious and questioning way: its “what” and “who” (and by, about, with, against, for, at, etc. whom) and “why,” in the context of a “when” and “where.” The “when” increases in pertinence if you’re “in the middle” as distinct (you hope) from end times. The “where” of this present (and past, and hopefully future) place of learning brings together all five essential eternal questions.

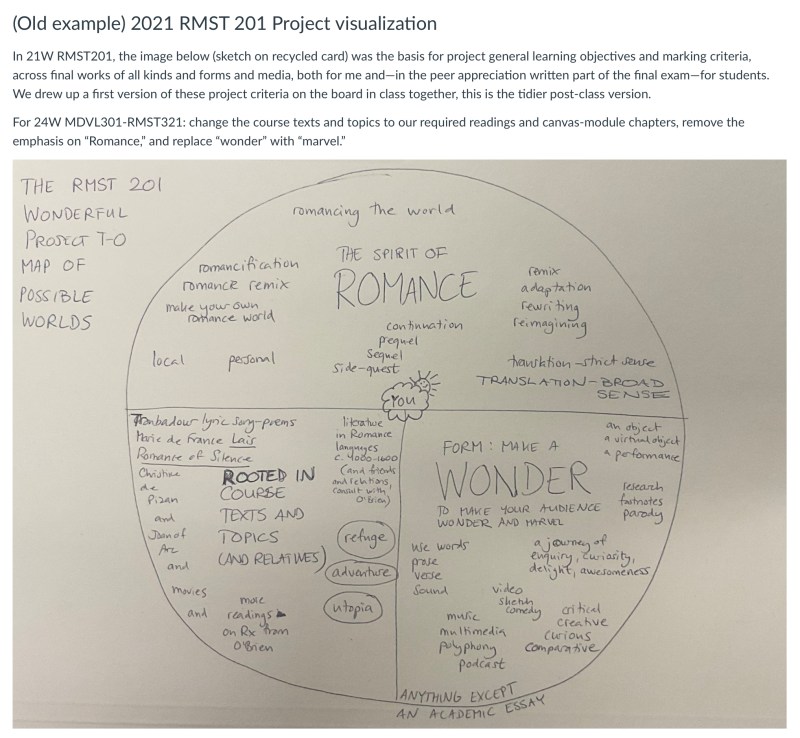

While my splendid colleague PM is on sabbatical, I have the honour of teaching a version of one of his regular courses; this one is a 300-level undergraduate cross-listed Medieval Studies and Romance Studies literature course. I’d been thinking about it since nearly a year ago, and the site’s central image dates back to that time, when I’d already decided on a central theme—which is a variation on this earlier “Marvels” course from 2018. For the last such course that I’d taught, RMST 201, 2021: “Introduction to Literatures and Cultures of the Romance World I: Medieval to Early Modern”—subtitle “An introduction to the main themes that shaped the Romance World as its different national identities emerged in the Mediterranean sphere”—I didn’t see a need to add my own theme, as the title and subtitle already provided plentiful food for thought. Like in that course, in this one all set required course readings would be online and free, with the option of printed editions for those who preferred; this third central structural element was the part that took the longest in course design. Readings for this course are in English translation; I also provide recommendations for versions in French and/or the original language.

The “Later / AOB” section of my To Do List has had, for two years now, a note to add a posthumous write-up of RMST 201; it’s at present only on Canvas, with restricted access. This tells you something about my state of burn-out in 2022, and of slow recovery accompanied by bad working and living habits (overwork, unnecessary overwork, working too late at night then undersleeping, etc.), but also of an improved state of mind and well-being, or maybe we should just call it “being” in the interests of avoiding neoliberal unironic non-performatives. As a guilty compromise, you’ll find its final project description towards the end of this post.

Course description

UBC Academic Calendar description

MDVL 301 (3) European Literature from the 5th to the 14th Century

Selected works from the 5th to the 14th centuries in their cultural and social contexts. Recommended pre-requisites: Third-year standing or above in the Faculty of Arts.

RMST 321 (3) French Literature from the Middle Ages to the Revolution

French literature through reading and analysis of translated works.

Description of colocated / crosslisted MDVL301- RMST321 2024W2 version: “A World of Marvels”

Marvellousness (mirabilis, merveille, merveillos) suffuses French and global premodern literatures, crossing borders of place (modern nation-state boundaries), time (early/late), form (literary genre, type of artefact), audience (social class and occupation), and register (high/low). From monsters to miracles, from mysterious other-worldly beings to marginal drolleries, imaginative marvels and their preservation through storytelling helps us to understand perceptions of pre-modernity, a history of those perceptions, and their continuing place in our present world. This course is for anyone who is interested in speculative fictions, escapism and consolation, playfulness, the weird and the awesome, beauty, and the delights of dark humour and satire.

Our adventures will focus on the imaginative worlds of some French texts from the 12th to the 18th centuries (CE): Marie de France’s Fables and Lais, the anonymous Aucassin and Nicolette, Jean de La Fontaine’s Fables, and the fairy tales of Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont and Charles Perrault. We will also encounter bestiaries, encyclopaedias, universal histories, fables, saints’ lives, maps, almanachs, books of hours, lyric and debate poetry, games, miscellanies, and manuscript marginalia. While our principal focus will be the close reading of literary works, we will also consider their context and transnational influence; the historical landscape in which these landmarks are situated; the cultural background against which their actions are staged; and their relationship to an integrated creative and intellectual environment of visual and plastic arts, music, ideas, technology, ecology, medicine, and science.

Classes consist of interactive lectures interspersed with discussions. Weekly topics and recurring themes include: perceptions of the natural world, creation and creativity, miracles, enchantment, other worlds and the other-worldly, dream-visions and mysticism, the fantastic, automata, metamorphosis and hybridity, apocalypse, nostalgia, utopias and other alternative worlds, and intelligent life.

Prerequisites

Informal recommendation: as this is a 300-level course, it will entail reading, analysis, and independent research.

Informal prerequisites: a sense of curiosity and an openness to wonder.

The main chronological structure of “A World of Marvels” is three chapters, each of which pairs up a medieval and a post-medieval French text (read, for the required version, in English translation); our course central question, in the French style, is: “what is a marvel?”

- week 1: introduction

- angle of approach to the idea of the marvel: words and marvels

- texts:

– 1 the course site thematic image, in conjunction with the course structure and with

– 2 our land acknowledgement; thinking about the latter deeply and seriously, in relation to teaching and learning about literature(s) and to what it means to imagine and (perhaps therefor) to be human

- weeks 2-4: chapter 1 – beauties and beasts

- angles of approach: what is a marvel?

– 1 marvels as material objects and moments in time

– 2 the marvel as metamorphosis in movement

– 3 the marvel as miracle and metaphor - texts: Marie de France, Lais – Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont, Beauty and the Beast – Jean Cocteau, the 1946 movie therof

- angles of approach: what is a marvel?

- weeks 5-8: chapter 2 – sleeping beauties, dreaming woods and otherworlds

- (week 7 is our reading week)

- angles of approach: marvels in action

– 1 expectations of dreaming woods and sleeping beauties

– 2 adventures in other worlds

– 3 other other worlds - texts: Aucassin and Nicolette – Charles Perrault, Tales and Stories of the Past with Morals (Tales of Mother Goose)

- weeks 9-12: chapter 3 – the (beautiful) power of fables

- (week 10 is a week of project check-ins replacing regular class)

- angles of approach: three degrees of fabulousness

– 1 superficial and blinding or enchanting wonder

– 2 narratio fabulosa, surface and interior

– 3 shapeshifting, translation (strict and broad senses), a network of textual kith and kin that fabricates a larger “in the (medieval) middle” - texts: Marie de France, Fables – Jean de La Fontaine, Fables

- week 13: conclusion – worlds of marvels, revolutionary marvellousness

- collective supplementary readings and wider discussions:

– French colonialism, the French Revolution, and after and beyond

– the end and apocalypse of pre-modern and early-modern merveilleux

– these subversive marginalities’ afterlives, fabulous resistances, and transnational inclusive kithy solidarities: feminist, subaltern, postcolonial, Indigenous, and ecocritical continuing histories

- collective supplementary readings and wider discussions:

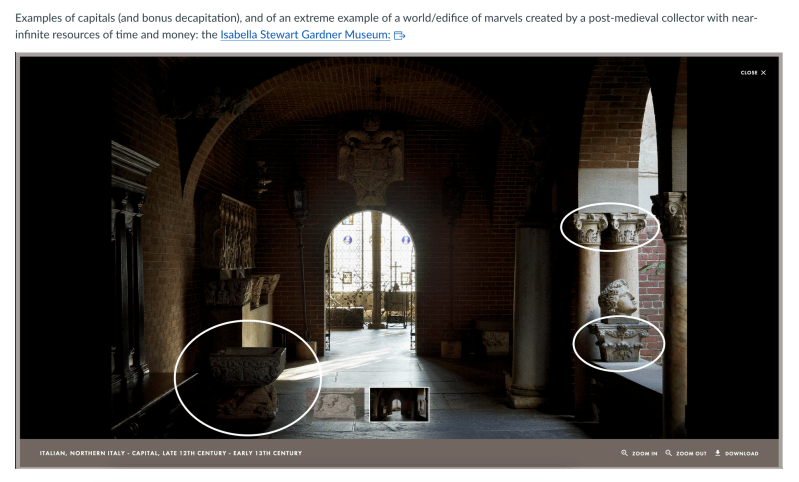

The course structure of “chapters” wasn’t intended in a bookish sense; although, as often happens, I’ve ended up with a course design that looks like a book—be that fictional novel or non-fiction academic monograph—to which I’ve long considered a course and its design and shape to be structural analogues; a live action version, and interactive and improvisational, unpredictable, co-created with course participants. Rather, I was thinking of the architectural chapiter or capital in our central course image.

“Student-centred learning” has so long been pedagogical convention, for better or consumerist competitive capitalocene worse, that it’s become orthodox dogma and, as such, as unquestioned as are its own history and its place within the larger histories of education and learning. It’s not exactly a new departure to move to learning-centred and knowledge-centred learning (see: Ken Campbell’s “seeking” as radical pedagogy), and to incorporate much older senses of “communicative” and “experiential” and “mindful” learning that are collaborative, creative, and contribute to community and culture; to sustainable and sustaining thoughtful ecosystems. This course and its learning aim to do that and more; it took me a while to see what that central course image was saying, and of course I’m not sure that I understand all of it, and I still don’t get whatever it was that my mind was doing when it said “yes, that’s The Image.” Here’s what I understand so far, as a rogue indie alternative pedagogy exercise, this year’s extension and applied practice of the Ken Campbell Pilgrimage / Retreat that happens just before the start of every academic year.

This course is polyphonic: texts, me, students, and their projects. Its lines, voices, and parts flow in and out and around each other. Sometimes there’s concert, sometimes unison, hopefully harmony, disconcerting exciting discords, grace-notes, pace and pause, rhythm. (You’ll observe that the image is unfinished, its stems and shoots could grow in many ways and directions and entangle, and how it would be completed in hypothetical possible futures and with hypothetical possible hands is an unknowable unknown.)

The texts are our anchors, our musical bass line. My Wednesday lecture-ish sessions (the rhythm section? percussion that’s sometimes useful and sometimes annoying?) are intended to provide material (readings, interpretation, associative ideas) for the Friday discussion sessions, which are open to re-interpretation and to taking different directions, depending on student interests (and their associative ideas, side-reading, background-reading, and so on). These Fridays are an unpredictable thread in the fabric that we’re making together. Together, they/we will try to answer that course central question, “what is a marvel?” (The image is decorative and marginal; so are we, so are our questions and discussions, but the text as a whole is the more beautiful and indeed marvellous because of its marginal elements. The central artist-figure is a monstrous hybrid, its snail-shell an infinite cornucopia, working its magic on other monstrous hybrids, at the moment of a vegetative nature but who knows what they would grow into and what/who might emerge from their flowers.)

The course full title isn’t just “marvels,” though, it’s “A World of Marvels.” “What is a world?” and “what is a world of marvels?” will be answered by the students, the “pillars” of our course, through their creation of projects as “capitals” and our assembly of them into a “world” (and metaphorical building) at the end of the course. The final exam isn’t just a coda after the submission of final projects; the culmination of the course is our “festive fayre of learning anti-exam” and its accompanying peer appreciation. (The radial spokes in the image are of an ambiguous nature; flora or human artifice, stems or architectural supports; and why not both, in this other world? The central artist-figure is unfurling from a hidden dimension behind the page, and the whole marginal ensemble is breaking through into our own / the reader’s dimension and world. Let’s be clear that the figure isn’t me, nice though that would be; it’s an allegorical representation of learning. The page and text are the bridge that connects us and our various worlds, and the gateway that opens up knowledge and potential future further knowledge; bridge and gateway both, underground rhizome and skywards giant beanstalk, both and more in this other world and its network of further other other worlds.)

So: Let’s think of course assignments not as being for punitive or grade-awarding purposes (or, as instructor-centred pedagogy or institutional-system-centred anti-pedagogy) but as the students’ voices in a course. Now, I don’t usually do student presentations, in the traditional way: our classes are too big for this, no-one listens to each other, everyone hates it. Well, that last part isn’t true, I exaggerate: some people love presentations, some value them, some think that it’s useful. I think that it’s not the presentations themselves, and their public speaking element, that’s useful and important; rather, it’s explaining something to someone else. I like making and performing (or whatever the word is) presentations, I have no fear of audiences, but I’m aware that’s not the case for everyone and I’m aware that traditional presentation formats have a tendency to dumb down knowledge and to over-value personal reaction to performance anxiety and stress. Our central problem, though, is our class sizes and how to resist scalability in its usual upwards sense by attempting scalability downwards: ensuring that the audience for any presentation (and discussion thereof / workshop thereon) is maximum 8; trying to replicate something akin to a seminar.

I have made compromises in the past, for presentation-assignments, as a lot of my teaching is in large courses that are taught in multiple sections, with a teaching team working with/under a course coordinator (a responsibility that’s also been part of my own work), and sometimes a presentation of some sort is part of that course. The key elements that should translate:

- attention: as small as possible a number of presentations in a session (3 longer or 5 shorter seems about ideal)

- a pre-circulated topic to help that attentive focus, and at least 50% of the session time for actual real live discussion

- feedback: peer appreciation, for ensuring responsible attentiveness and nurturing a mutual-aid intellectual community

In French language courses, I’ve adapted presentations and some oral exams to being individual or small group (up to 3, 4 maximum) 5-10-minute video which students then share online, in a secure LMS (UBC Canvas) with access just for that class. We then have a viewing session / watch party in which groups of students, or groups of student groups, watch all their group-of-groups’ videos together and discuss and comment. (I’ve long wanted to do a second stage of the exercise, in which students record themselves watching the videos together and discuss (and banter) in French, like Googlebox.) Done in classes of up to 40. Approximately; workable up to 50 or 60, in “pods.”

In Medieval Studies and Romance Studies courses and further back in time some French language, literature, and culture ones, I’ve also adapted presentations to a round-table session, maximum 5 minutes per person and maximum 5 speakers, with topics and abstract pre-circulated, and the second half of that session is discussion and Q&A in small groups. I’ve done this with around 30 and could scale it to 50+, as a “mock conference” final week.

“A World of Marvels” has two streams of student contributions to the course, as co-creators of our collective contributions to knowledge.

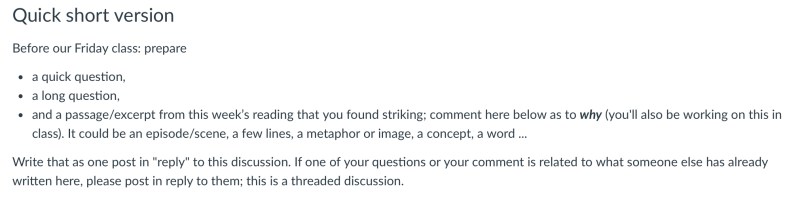

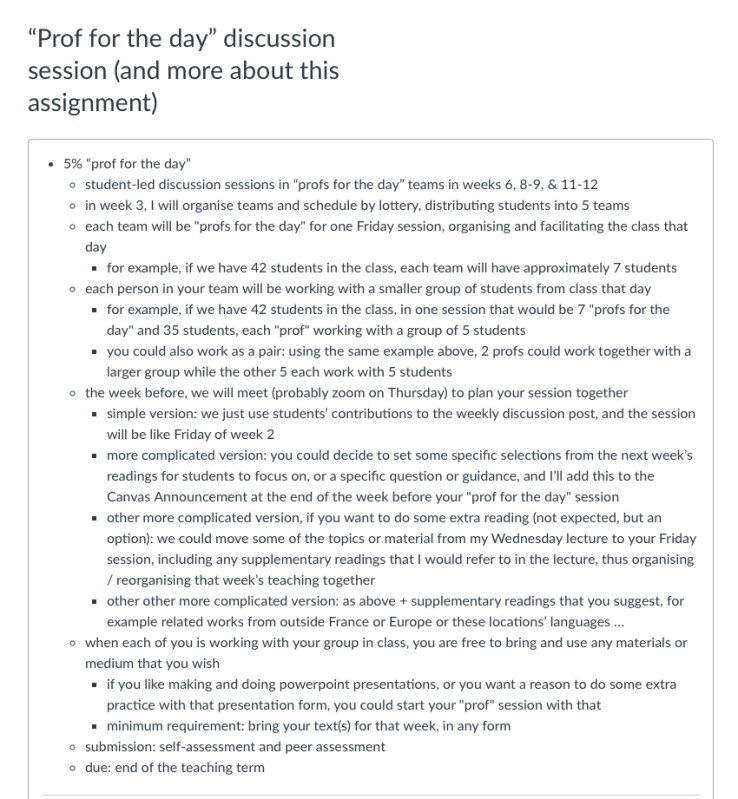

(1) During the teaching term, the second session of the week is a discussion session. Classic format (screenshot below). In later weeks in the course, the students run this, in teams, as “prof for the day” sessions: my thanks to a student in a previous class like this, Rachel Chen, for coming up with the name.

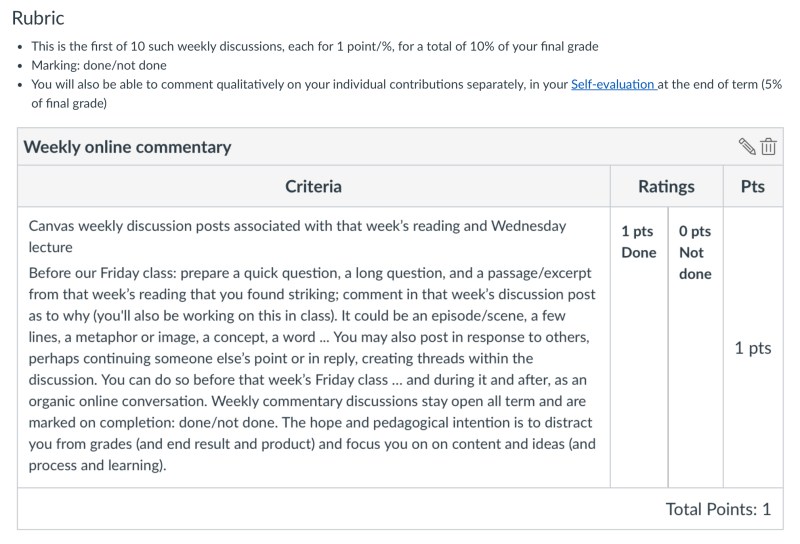

Here’s how these weekly discussion sessions are graded:

”Prof for the day” is graded in what I like to think of as “responsibility-based grading”; reminding us that this doesn’t need to be a commodifying, quantitative grading (or indeed some kinds of ungrading), but it can be instead about valuing work, returning the qualitative and human and valuable, akin to words in French like évaluation and évaluer.

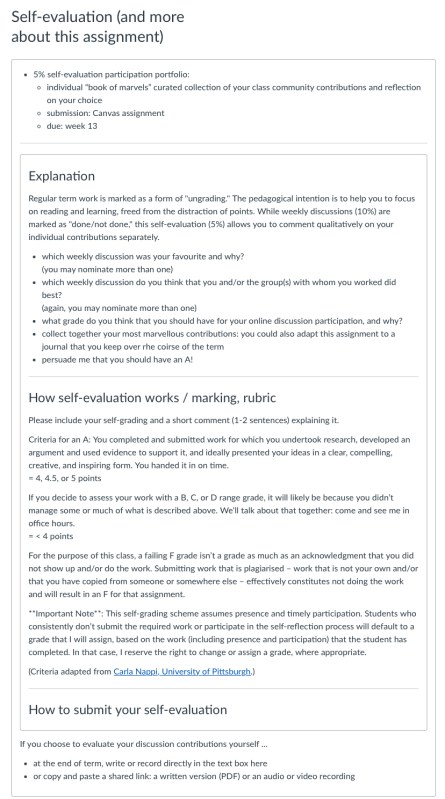

Students also reflect on their contributions at the end of term:

(2) A scaffolded project runs alongside the class-course, in polyphonic flow.

In certain weeks we replace classes with project-group meetings, where they come to my office, instead of the classroom, and we talk in comfy chairs with books around us, like civilised humans. We had a first one in week 4 of term, instead of the discussion session (and students contribute to that discussion online when they’re not in their meeting). The second meeting (technically stage 3 of the 5 stages of the project) is in week 10 of term, in lieu of both our classes that week.

The very last stage of the course is a final (anti-/un-)exam, in two stages: the first is a festive fayre of learning, the second is a write-up to be submitted in the 24 hours after the exam.

This course’s focus is on genres often relegated to minor/marginal positions (so: not romance or novel, not individual-single-author, not Big Famous Books By Big Famous Names) and forms of critical and creative work that aren’t the standard/classic/traditional academic essay: so writing (and other expression of ideas) in the course, including this last one, tend towards the commentary.

Here’s what the course and its project look like. The design might be perceived as a marvellous project in its own right; but who knows what the course as a whole will be at its (and our, as a class community) wonderful end?