At the University of British Columbia, summative peer review is an established practice in the overall evaluation of teaching. Faculty members typically participate in both formative and summative peer reviews of teaching as part of their career progression and growth. […] The formative peer review of teaching (PRT) is a process intended to support instructional growth and collegial conversations about teaching, as well as enhance student learning. In the PRT, peers may provide feedback on various elements of teachings [… including] Self-assessment documentation such as a teaching portfolio. Peer review of teaching, when focussed on growth and development, is a reflective and collaborative process in which the instructor under review works closely with a colleague or group of colleagues to discuss teaching. Though the process outlined [… ] is unidirectional (i.e., a reviewer giving feedback to an instructor), we highly encourage you to consider a reciprocal peer review process where instructors observe each other’s teaching, reflect on what they learned through the observation, and share feedback […] individual reflection on, and inspiration for improvement in, one’s own teaching.

—UBC, Centre for Teaching, Learning and Technology > Formative and Summative Peer Review of Teaching

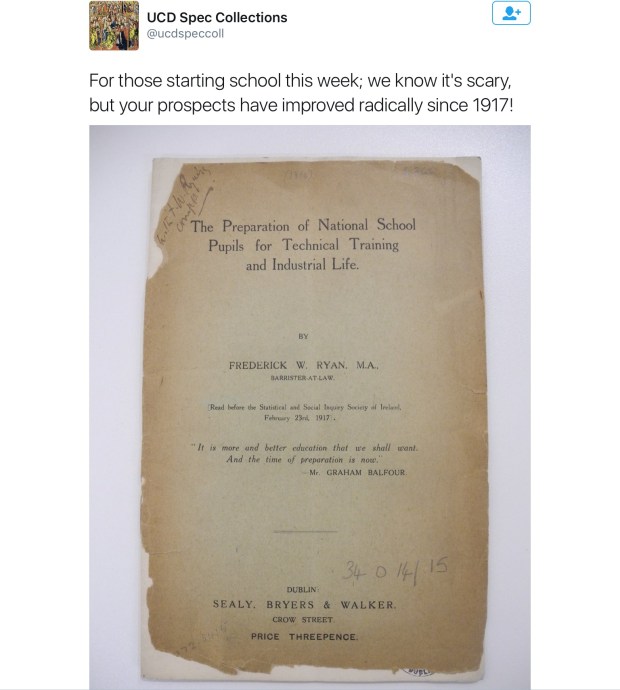

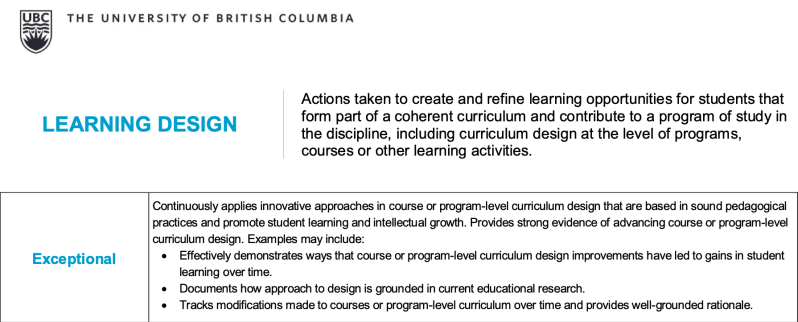

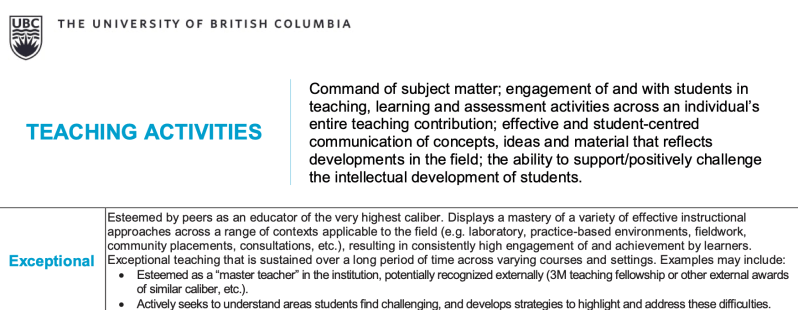

Here’s what that looks like, from the Summative peer review of teaching rubric:

(We could talk about the above further, but this is not the time or the place or the point.)

Some reflections follow below, comparing and contrasting two related courses, thinking about them after their end. References for the courses themselves and for the thinking behind and before them:

- (January-April 2025)

RMST 321 / MDVL 301

the course: https://blogs.ubc.ca/rmst321mdvl301in2024/

course design notes: https://metametamedieval.com/2025/08/23/on-course-creation-intelligent-artifice-theoria-poiesis-praxis/ - (September-December 2021)

RMST 201

the course: https://blogs.ubc.ca/rmst201in2021/

course design notes: https://metametamedieval.com/2025/08/22/on-course-design/

In this blog’s previous post, I talked a little about how these courses are related: thematically, structurally, and through their assignments. They’re essentially developments of an idea and approach that goes back some fifteen years to the start of my time here at UBC, a place which has encouraged creative innovative teaching. (Mostly. Some courses and areas less so, some in certain ways and not others; for practical reasons of the subject-area, its characteristics, the way in which a kind of knowledge is organised, how it works and thinks of itself, what it does, and how people do and live it. Natural variation in a whole ecosystem.) Here’s the historical context behind these two courses:

- (January 2010— )

the rest of the course-family / aunties and ancestors:

https://blogs.ubc.ca/julietobrien/course-creation/#rmstmed

What have I changed along the way? What would I change in the future? Why / why not? Mindful that “change for change’s sake” might looks like the desirable “progression, growth, development,” but only in a simplistic superficial neoliberal sense; it’s an example of the logical fallacy of argumentum ad novitatem.

Plus ça change … via @PhilosophyMatters

ASSIGNMENTS & RUBRICS

I’ve written variously on this blog over the years about portfolios, scaffolded projects, and the festive fayre of learning anti-exam; and about them as innovative applied medievalism. The big change this year: I had the time and mental space to develop fuller guidelines and rubrics. I’ve been wanting to do this for years, and to have them ready at the start of term, albeit retaining the potential for future flexibility. It’s important for students to know what they’re getting into while they have time at the start of term to drop a course … or to tell their friends so that they add it.

The compromise had always been working these parameters out with students along the way, so the base for this year’s work was collecting and consolidating old notes (often in notebooks, often hard to read) and information from email correspondence. What’s not changed and I hope won’t: it’s always been a delicate balance between clarity on expectations and enough opacity to discourage brown-nosing, a box-ticking mechanical attitude, the impoverishment of quantification, the delusion of “pure” metrics, accountancy pretending to accountability, etc.

Working out exact guidelines and rubrics with students was good, at the time and for this new version, as it meant that assignments were co-designed with students. The version that you see now, to my mind my best so far, is as much the fruit of students’ questions, reflections, and intellectual labours.

What would I change? The weighting of each stage of the scaffolded project. I change this every time, talking with colleagues (in my own department, in other departments, elsewhere outside our university). I’m never sure that I’ve got it right. I talk to students; we’re agreed that a design principle should be that there’s proportionality between work done (time and effort) and points / grades (remuneration, to keep the analogy of labour rights and social justice). I need to ensure that there’s enough room for equity, and that grading encourages communitarian mutual aid (rather than mere free-market competition): from each according to their ability, to each according to their needs.

QUIZZES & TESTS

The two courses above have no quizzes or tests. This is not through ignorance or incompetence; I do have both in language courses. (Both quizzes and tests, that is. Ignorance and incompetence I have like anyone else anytime and everywhere.) That’s a different story.

I once did regular weekly take-home online quizzes in literature classes, to accompany readings: I don’t now. Instead, weekly online discussion-posts that accompany in-class discussions.

Reasons for doing that kind of preparatory quiz before a text is discussed in class:

- to ensure that students have done the reading

- to guide their reading

- to check that they’ve noticed and thought about the elements in a text that I read as important

- so that when I lecture and we discuss a text in class, we can spend time on close reading and in our collective reading at a more advanced conceptual level; rather than taking up class time with basics of plot, character, etc.

Reasons not to do preparatory quizzes:

- Micro-managing reading and control textual interpretation

- Turning reading into an assessed task, attached to its testing, so that students will “study” for it in all the dreadful anti-knowledge anti-learning ways that they’ve been trained to do in schools and—alas—in too many parts of our university, even in some parts of Arts: memorisation of facts, regurgitation, task-completion, move on and forget about it; last-minute cramming; focus on point-scoring; rereading only for post-mortem grade-grubbing.

- Not treating students as responsible fellow adults, as people who chose to be and want to be in this class, putting into active practice a university’s respectful environment policy

- Disrespecting texts and reading: to have, instead, reading-guidance questions alongside reading, as marginal notes; not interrupting or punctuating it—which would effectively be my editing my version of a text and reducing it to a set of key points—and not in a way which is intellectually insulting and inappropriate for this level of work and thinking; what’s appropriate for reading comprehension in beginner-to-intermediate other-language-learning is not at an advanced level or in the university’s main language / lingua franca

Boring practical human reasons not to make take-home quizzes, of any sort, whose frequency means that they are numerous:

- Making quizzes is a tricky business: ideally, they should be fast and give immediate feedback; they should be fun and engaging, and interactively connected to the material (colleagues and I have been making preparatory quizzes like this for beginners’ French language for years, plus mini videos introducing readings and chatty comments along the way)

- Rapid feedback means automatically-corrected questions. Risk 1: over-simplification and reduction to yes/no, right/wrong answers. That’s simply not appropriate or acceptable in the literate—reading, thinking, critical—humanities and its kinds of knowledge, ways of knowing, and knowledge- and learning-centred learning.

- Risk 2: an extra 10 hours’ work to make a quiz that’s intended to take 10-20 minutes so as to include all possible imaginable answers and notes on each wrong answer. I’ve made quizzes like that. It’s unmanageable during term time, playing catch-up before each coming week, when teaching a full load of 3 courses. It’s unsustainable to do the supposedly sustainable version, doing all the preparation work the summer before: even when I wasn’t teaching in the summer, and definitely not now; teaching two intensive courses in part of the summer, the other part is officially free of teaching and has my statutory annual leave and therefore not for work.

- Non-automated feedback isn’t feasible if a quiz is done at home to allow a student to time and pace their own work; that would mean me being online 24/7, and ready to drop all other work so as to mark a new quiz coming in. I teach two other classes, I might be teaching that class, some work (ex. teaching, meetings) can’t be done multi-tasking as it requires 100% focus, and some work (ex. teaching prep) shouldn’t be interrupted as it requires focus for a longer extent of time.

- The kind of detailed individual feedback that was possible 15-20 years ago with a class of 15-25 students is not possible now, with our current and ever-increasing class sizes and teaching load. (Ask my home institution about the money spent, and over-budget, on WorkDay and the Integrated Renewal Program™; and ask about where the ever-increasing student fees go; and ask about parasitic para-academic and non-academic managerial executive administrative bloat.)

An alternative:

- a quiz that’s at a set time, so that I can do the feedback in a humane way: given the number of students and their range of schedules, the only possible time would be during class time

- but doing so weekly eats up our precious 3 hours / week of class time, time better spent on work that needs live contact

- and that turns what was a side-note to guide reading, a formative exercise in learning to read and training in its regular practice, into a summative test; which wasn’t the original point

- and we ruin a course that aims to be a guided reading-and-discussion group, akin to a book-club done well, as befits being about literature; of which reading is an integral part

A better alternative:

- It’s much more interesting for all of us for students to come up with their own questions and to discuss these questions and their choices; compared to punitive quizzes, it’s a better faster way to get students to read closer and deeper and broader to spur each other on, peer pressure and light friendly competition (like a game, I mean a proper fun game not the kind about point-scoring and winning), building community expectation, co-creating a class community: which is the crucial element that changes a course into an actual class proper.

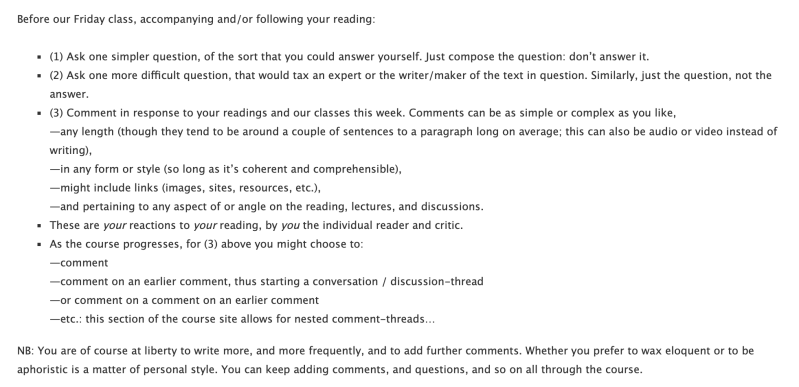

- Inspiration and best practices: The model of “ask a quick question, ask a long question, make a comment” has been standard practice in philosophy for decades; and variations on the theme for centuries, from students in class to research to generalised methodology to ontology.

- What this looks like: in the screenshot below, my most recent iteration, which looks like previous ones. One change: to open up “writing” to extend its communicative sense to AV. This was for two reasons, both technically “student-centred learning” in its proper sense, not the commodified consumerist capitalocene abusage; developing the idea through talking with students, and talking about how we all read. (1) Inclusivity and universally-accessible design. (2) Encouraging students to annotate as part of their reading, with a text open in front of them and a second device alongside. For some, that’s writing notes on the text; glosses, margins, footnotes. For others, writing in a journal. That journal can also be digital; and the writing alongside can be spoken. Try it: the easiest way is to place your ‘phone next to you, start recording, start reading, and when you think of something just say it; whether that’s alone talking to yourself aloud, or in a shared space with a group of fellow readers, where you record everything that you say—individual comments, conversation—like a watch-party but for a written text instead.

APPROACH

I’m not sure how to approach this. I have a sense that my approach to teaching, the how and why of it, hasn’t really changed; it’s always been there, it’s become clearer in my mind, and when thinking about it I always see other examples where I was already doing a thing before being fully aware of what I was doing; or it seemed like the most obvious or instinctive way to do something, or I’d met examples from other times and cultures, and then later I would find that some 20th-21st c. CE person had placed a label on it and made it “theirs” in authoritative-fallacy kyriarchical conquest, colonialism, and erasure for extractive-industrial purposes.

My approach was already there a long time ago, in learning about teaching from teachers in kindergarten onwards, and from parents who read to me. Reading fables, fairy tales, myths, and other speculative fiction. I learned some more about teaching when I was doing other work: as a bookseller, film-reviewer, librarian; less obviously, mostly through worst practices, as a serving-wench in the hospitality industry. Watching comedy. Listening to Ken Campbell over the decades. Donna Haraway.

Like many other colleagues who do the front-line academic work of teaching, the pandemic changed things: teaching and learning online. Now we’re at once post-pandemic, still in a pandemic, returned to normal and business as usual, in a new normal, and living in Interesting Times next door to our ever-evolving southern neighbo(u)rs. My learning about teaching was probably at its peak in 2016-23, thanks to online communities on what was then Twitter; these were real, and brilliant, global communities of practice, free grassroots organic rhizomal democratic anarchist maker-spaces, something that cannot be replicated by any institutional top-down construct. Where I learned about un-grading from Jesse Stommel, about systemic injustice from Sara Ahmed. I’m still grieving for the loss of that space and its communities. Give me time. I’m at the stage of awareness of depression, of starting to reach out to people again in other and offline ways.

What’s not changed: learning-centred learning as radical pedagogy

What’s changed more recently, that I noticed myself doing in that course earlier this year and in online teaching this July-August: ever more emphasis on the liveness of a class. That is, teaching itself as live performance art. This next section moves away from those other parts of teaching that are course and assignment design, structure, organisation (and what could be termed management and administration). Here are some notes, in no particular order, that involve thinking about teaching and learning as crucial live human activities, and thinking about GenAI, with behind them all the reading that we’ve all been doing and the conversations that we’ve all been having about it. (More on which next week. That will take the form of lists of links to readings and a hand-crafted curated collection of screenshots and images.)

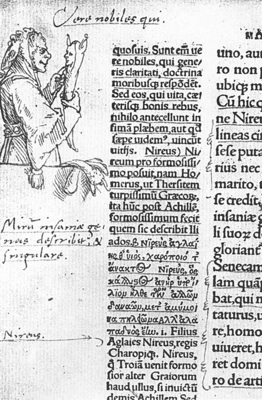

Hans Holbein, marginal drawing; Erasmus, In Praise of Folly 1st ed. (1515). Kunstmuseum Basel.

SOME NOTES

Student work policy draft:

Work for this course falls into three categories:

- assessed work, marked with feedback and whose mark contributes to your final grade;

- other assignments, marked automagically, small participation tasks like quizzes [mostly this pertains to language classes, and as far as possible doing these in scheduled class time – not relevant for rmst], that are marked on completion;

- your other work outside of class time: preparation, practice, etc.

GenAI:

- For (3), do as you will – this is in your “own” time and space anyway.

- For (2), some mini-quizzes will be open before and/or after class, we’ll also do them in class time; I’m not checking but would discourage you from using GenAI [or other tools – automated translation, for example] because you’ll get the point for doing the thing anyway, why not learn while you’re doing it, and learn how to learn as a bonus? Other tasks like discussion-posts will be in class collegially; tools and their use will vary depending on the nature of the task. Some, for example, will be about intelligent tool use: starting with how to find a word.

- For (1): no GenAI for assignments that are marked (by a human – who will also not use GenAI tools in her marking). Such assignments will also be: closed book and in scheduled class time (or, for a final written exam, during the scheduled final exam period), with an oral presentation or live active experiential element, and/or with a peer evaluation component.

General note: You are an intelligent human. I respect you as such, as an intellectual peer and fellow member of the university as a knowledge-making learning community; we are a companionship of seekers. You have choices and a beautiful mind. Use it. As with any other matter of consent and adulting: make careful, thoughtful, mindful, informed, educated, ethical choices. Use whatever tools you wish for learning: it’s your learning. But do so responsibly.

Readings: radically online with open free resources – gateway-medievalism vs gatekeeping-medievalism (you can only touch the pretty things when you’ve successfully completed training in background history, palaeography, codicology, philology, and the original languages)

Inclusive ecofeminism is an approach from design to “delivery” into its next stages in development, triskelion apprentissage en spirale; learning-centred for ex. designing projects and their rubrics with students. In class, storytelling; radical liveness and performance – in rmst and summer online teaching, depth and breadth, bigger more complicated ideas allowed their time and space. Knowledge-centred learning respects its content / material / substance / subject-matter. Long-arc and rhythmed storytelling, subplots and side-quests and all, is an antidote to canned videos, tiktoks, and the misplaced pedagogical orthodoxy of super-structured micro-managed 5-minute activities for 5-minute attention spans. This is a university. FFS.

The mechanical (in the service of anti-humanities anti-thinking, inhuman, unthinking, quantifiable, metrics) is as much our foe as machine learning – instead, more work, more feelings and feeling, more human: “imagine for a moment” and “hold that thought” and “stay with the trouble, sit with it, be in the moment.” GenAI is a tool, like any other, just more obviously open to misuse, and with misuses and abuses that are greater, through ignorance, stupidity, thoughtlessness, unthinking – my deeper fear around GenAI use in my immediate environment is as much about the increasing artificiality and decreasing intelligence of human(ish) users and the systems that they build, manage, and run; mechanical and with no critical thinking as that means questioning, interpretation, judgement, and responsibility. The very human attraction of irresponsibility and blaming a faceless authority isn’t new (Graeber on bureaucracy). Better still, transcending agency responsibility humanity, to have power and abuse authority by hiding behind The System. Including and beyond the university, existential worry: AI (generative and otherwise) use in large national databases supporting the pillars of a functional society, and (in the first case) directly: education, healthcare, social security, environment, taxation, representation, protective regulation, clean air and water and energy.

(Parenthetically let’s not forget the minor niggles and quibbles of energy and water use, environmental sustainability, climate disaster, etc. In a university that prides itself on its green credentials. Mind you, in a general educational culture of neoliberal credentialisation, a university whose flagship humanities research library is mostly filled with finance and accounting and senior management executive offices, and a city whose local mayor digs bitcoin mining.)

We need to talk about LLM GenAI that’s as useful a tool as any other language support: glosses, dictionaries, and indeed written texts themselves. For plurilingual people. For disability, fatigue, sustainable work. Online chat and support aren’t new (fun fact, I first did online moderation 30 years ago); they can be a supplement, but they can’t be a substitute. Well, they can be in some fields: sales, marketing, and customer support. I’ve long preferred dealing with sidebar chat rather than a scripted apparent human on a telephone. And the present catastrophic state of the Hollywood film industry is such that it’s hard to tell if yet another franchise is down to delegation to AI; or what happens when finance, marketing, and branding executives take over full control and are enabled in their delusions of artistic grandeur. If you’re teaching well—properly, at all—then your liveness, response to changes, and thought in improvisational action distinguish you and your work from a telesales operator, bot, or simple automated online chat. What makes what you do different: reflection, interpretation, critical judgement, and art.

We can’t teach people the way we’ve done in the past. The original experiential learning, knowing by doing and through the first-hand experience of travel, was always a rare exclusive expense reserved for the very privileged; or for brave / foolhardy adventurers. (Both are of course also ableist and sexist; and all that is the opposite of inclusive.) Meanwhile also: there’s storytelling. But also: books! And, with increasing access to literacy and libraries, and to free basic education, access to knowledge. It did / does mean work, heavy imaginative work. But also: other media! Complemented, in Montaigne’s ideal education, with an accompanying guide. We know that throughout human history (as the classic formulaic student essay would grandly hand-wave) the ideal has always been a dedicated individual personal tutor; thinking about this in summer reading, Marguerite Yourcenar’s Mémoires d’Hadrien, its depiction of a luxurious version even for a Roman emperor … Bots of old and ChatGPT of new have potential, used well and wisely, as personal tutors for students (first witnessed done well and wisely by a computer science undergraduate back in 2023), and as personal assistants for all workers whose stuff is ideas and their expression and communication. The latter has been feared as an end to support work akin to historical antecedents: 1980s secretaries being replaced by personal computers, 1950s operators by telephone switchboards, messengers and signalling by telegraphy and telephony, 19th-20th c. artisans by automation … and remember the deskilling, reskilling, upskilling; the unpredictable next; but overall, contributions to the development, and developing monolithicity, of capitalism. I have no answers or solutions or predictions, and the few more-or-less-good possible future examples that I’ve met in SF have been complicated: Star Trek, Doctor Who, Octavia E. Butler, N.K. Jemisin, Gwynneth Jones, Nnedi Okorafor.

I have Issues / Thoughts about inclusive and informed consent and second-mover advantage; against GenAI as unthinking lazy fad-following, ironically in an attempt to be seen as (thought)-leadership; this 2020 writing feels prescient. I’m in at least two minds: balanced with the potential for responsible use for intelligent thought, as and when needed—responsibility entails selection and economy—so: as intelligent tool-use (and pro-EDI) to liberate time, energy, mental space, and human resources for learning. Wasn’t that supposed to be the whole point of technological advances and the singularity: the liberation of humanity? Whether doing so is part of that or counter-cultural resistance, let’s reclaim humanity *and* the humanities as being about learning and understanding, entendemen as education. Towards Le Guin’s Ekumen, Iain M. Banks’s Culture, Star Trek …

Space: while we’re at it, let’s rebuild the venerable ancient space of education: libraries as places for learning in live active physical motion, for browsing erring adventuring, serendipitous encounters happening-upon, connection-forming, concentrated reading (in many ways and senses, including skimming) in situ; and with only limited short-term borrowing (and making notes), that intellectually vital movement, for which closed stacks and measuring borrowing not footfall is disastrous.

More space: The space of learning is a mental one of imagination, hypothesising play, reasoning that’s fun but also work, exercise, like any other there’s joy endorphins mood satisfaction pleasure, feeling, feeling anything, feeling alive – this you miss if you skip process and practice, Aristotle’s basic theoria-poiesis-praxis of human activity as, here, learning.

Summer reading that’s overshadowed any other reading about AI (or teaching and learning and reading and the point of it all) and been haunting me since May: Elizabeth Bear’s short story “Terroir,” in her Best Of anthology (2020, Subterranean Press). Go to your nearest public library and borrow it, while we still have such places for free access to knowledge. Tolle lege.

This is not an essay. There will be no conclusion.

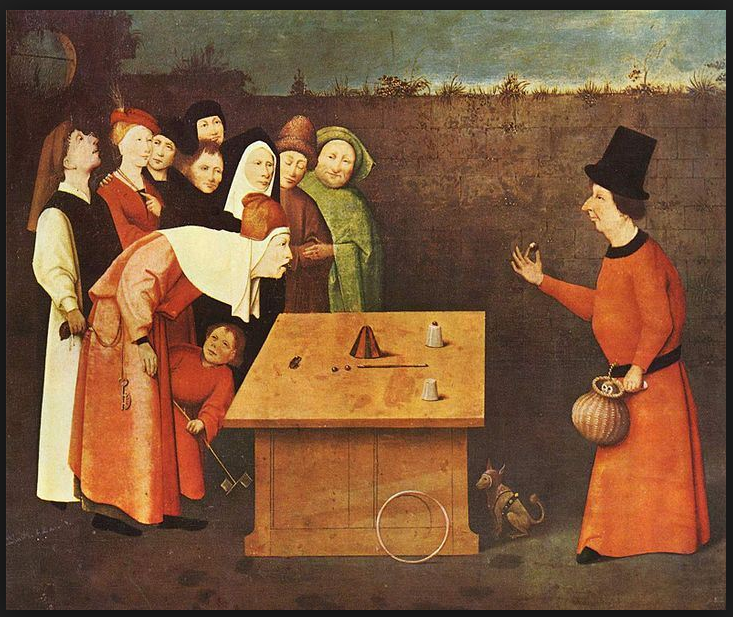

attrib. Gielis Panhedel, previously attrib. Hieronymus Bosch or his workshop, The Conjurer (c. 1502). Musée municipal de Saint-Germain-en-Laye.