Summer 2024 was the first time in ten years that I had taken my full contractual month of annual leave to travel and spend quality time in the nearest approximation, by conventional standards, to what counts as “home.”

I’m with my sister. Birds sing. Ducks swim. Capybaras relax by a pond in Flamingoland in the north of England. It’s home and holiday at the same time. That’s not confusing or complicated, it’s simply happy. (Maybe for capybaras too.)

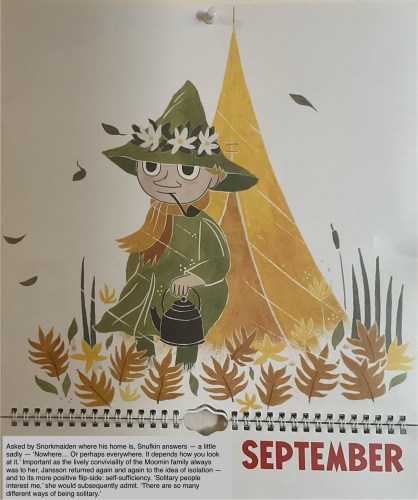

By most people’s definitions, I don’t have a “where are you from” and I live in a place where I can’t “belong”: the traditional, ancestral, and unceded territory of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam) people. I share that inability to belong here, of course, with everyone who has settled here over the last 150 years. That can be as unsettling for sojourners as it is for settlers; albeit having spent all of my life in elsewheres—being “from” and “of” places that no longer exist and maybe never did or could, including a postwar-reconstruction transnationalist pacifist idea of Europe—I’m used to not fitting in properly.

It’s an oddly comforting discomfort, that here, for the first time, I am in place where I can be content in being consciously unsettled.

Being displaced is a highly liveable human condition anyway, as a “place” doesn’t have to be a physical space and we can live in multiple spaces, sometimes all at once when you’re in a human habitat that’s already a multiverse—try observing all that you walk through just on a commute to work— and with the more-than-human worlds of reading and learning—consider your several TV series, books, podcasts, radio shows, and internet rabbit holes right now.

Those last times of being fully away abroad (and/or “home”) in 2013-15 had not been vacations: punctuated by moving around and obligations (which I don’t want to talk about here, complicated and angering), missing the defining “vacant” element. I hadn’t realised until this summer how much I need to be able to leave and to have the leisure to do what I please. That can be alone, or it can be being alone together with the right companion, such as The Beloved.

Last summer I couldn’t leave this country as I was waiting for a crucial document to be renewed.

In 2022, I was in Europe for a little over two weeks, sort of undesigned (by me) and with a broken ankle; an uncomfortable trip cut short by a calamity but glorified by a few days in a new country (Norway) and a few days in my favourite Amsterdam museums. I didn’t go anywhere in 2021 or 2020.

2019 was eight days in December, of which four days’ travelling, an anti-vacation as I was also doing course coordination preparation work and writing a conference paper for January. (Pre-pandemic Decembers were pretty similar, usually also with exam marking, and at the most expensive time of year to travel. This was unsustainable in too many ways.)

2015 was the last time I was “back” in Belgium, where I grew up, That summer was a month away but in many places, chopped up, lurching around, an inadequate rhythm to that movement echoing a lack of quiet and quality to time. I managed to have a scant few hours doing what I wanted to and missed. Being in my favourite museums, where I’d spent so much of my growing-up, with artworks that feel like part of me, that’s where I have a sense of “belonging” and “home.” Walking around, for hours, at my own pace and not looking at the time. Being out of time, precious moments. I say “managed to”: obligations again, anger again: part resentment, part blaming myself for reacting to manipulation by regressing to bad old patterns (and I don’t want to talk about it more, not yet anyway).

I really, really, really needed a decent holiday abroad. (Or at home. Whatever we’re calling elsewheres.)

This summer I saw family and did no work, and we did fun holidaying things. Some were outdoors in parks and at the seaside; some in urban and suburban spaces being regenerated, some degenerating back to a state of nature. An arboretum co-managed by Royal Botanical Gardens and by a so-called noble aristocratic estate; ethically complex for a republican (in the leftist sense) redhead if the result is protecting red squirrels and decolonising an environment. Allotments. A riverside weird fairy garden, caringly maintained in gently dank rumpledness, or perhaps that’s the fungal spirit of the little people when we’re not looking (I took photos of the garden, which have disappeared). Dells and glades in twilight zones between man-made and not. An outdoor art installation, overtly co-created.

With my aunt in London for the first decent length and intensity of time in at least a decade, we walked Hampstead Heath and I had days, blissful days, in the British Museum. And I spent proper serious quality time in Brussels, most of it in museums and walking around. It was the perfect time to travel there leisurely as this year is the centenary of The Official Start Of Surrealism and its October Manifestos, so there were wonderful exhibitions for even more museum-meandering, the meanders even more oneiric; though to be unfair to the birthday celebrations and to Great (Angry Young) Men, Belgium is and always has been surreal. Especially the medieval Belgium of Reynard the Fox, Béguines, gothic buildings and bande dessinée, and carnavals.

Here’s a small sample of real live Brussels surrealism in the wild. A mammoth is underground in the metro. A tram that doesn’t exist is going in the wrong direction. A bowling alley runs amok. In what used to be a fish market on solid ground, giant ducks now swim.

A public art installation created by Jean-François Octave to commemorate the centenary of Marguerite Yourcenar’s birth is Tardis-like and inside it the outside urban soundscape shifts. Through the last twenty years the labyrinth has grown beyond the original architectural intention of “des vides et des pleins” into a fuller gateway to underworlds and otherworlds (193 avenue Louise, Brussels, Belgium).